//My Password is passwordispassword

In September of this year a large dump, approximately 5 million, of what was claimed to be Google account usernames and passwords was dumped onto the internet. While Google’s own analysis of the dump showed that only 2% of the accounts would have worked to allow access into Google/Gmail accounts (see: http://googleonlinesecurity.blogspot.com/2014/09/cleaning-up-after-password-dumps.html) I still found it interesting to analyze the password dump as it offers a glimpse into how people choose their passwords…I guess I can’t shed the pen tester in me or my love of breaking and analyzing passwords.

In the past (circa 2006-7) I completed a similar analysis on ~100k Active Directory cracked passwords that were harvested through a few pen tests in 3 different industry verticals (energy, oil/gas, and healthcare). The idea was to get a view into not only how people chose their passwords but also to understand how to break them more easily. At the time the only available password dumps and research I could find was being done on passwords from websites (e.g. myspace phishing). I wanted to see how corporate users were choosing passwords and not analyzing how some 12 year old chose a password of “blink182”.

The main take-aways from my research on ~100k corporate passwords were:

- 99% of the passwords were less than 14 characters in length – and a majority were 8 characters in length

- Passwords generally had a root that consisted of a pronounceable (read: dictionary) word, or combination of words, followed by an appendage

- The appendage was:

- A 2 digit combination

- 4 digit dates (from 1900-2007)

- 3 digit combinations

- Special characters or special plus a digit

- The root or pronounceable word was rarely preceded by the appendages I listed above, but in ~5% of the cases the passwords either started with the appendage or were wrapped in appendages

- Through examination of password histories and phishing attacks I was running back then, I noticed that when users are required to change their password they generally change the appendage and not the root (i.e. password01 becomes password02, and so on)

It also became quite obvious as to why the majority of the passwords were 8 characters in length once I reviewed the GPO that was applied to the domain (or users OU) that dictated that the minimum length be 8 characters with complexity enabled. Why a length of 8 and complexity enabled you may ask? Well, likely because Gartner recommended this as a length due to the amount of time brute-forcing an 8 character complex password using CPU-based methods was considered adequate, unless of course we are dealing with LM hashes as was the case in my initial research. GPU-based systems, as we are well aware, have no problems brute-forcing their way through 8 character complex passwords (and this was as of a few years ago).

So, on to the current password dump of Google usernames and passwords. While I realize I discounted research on website passwords earlier I made an assumption here that at some point all of those corporate policies and awareness trainings would make their way into our everyday “password” lives and into our website passwords. Plus, I already had a copy of the plaintext passwords, there were a lot of them, and I didn’t need to spend any time breaking them.

First, some raw numbers and my technique:

- There were just under 5 million passwords in the dump, of which I sampled approximately 20% (1,045,757 to be exact) for analysis. I made the assumption that this would be a statistically relevant sample and the results indicative of analysis of all ~5 million passwords

- I removed all 1-2 character passwords, leaving me with passwords of 3-64 characters in length

- I had to spend some time cleaning up the dump, removing passwords that appeared to be hashes (and not plaintext passwords) as well as removing lines that were obviously mis-prints (i.e. website addresses versus passwords, extra line breaks and the like…)

- Prior to removing duplicate passwords I did some quick counts on both common or funny passwords, and here’s what I found:

- A very small number (~3,700) contained a swear word. I’m not telling you what I searched for, but the reason I did this was I found these to generally have the funniest combinations both in this current analysis as well as the corporate passwords mentioned above

- A smaller than expected number of passwords (~10,500) contained “pass” or “password” in the password

- The use of 1337 and 31337 is still a thing (albeit small) with ~2,500 passwords containing those strings

- Nietzsche may have been correct and God may be dead as ~1,900 passwords contained the word god

- There were 255,284 duplicates which resulted in a final (de-duped) password count of 790,462

Another reason I wanted to complete this analysis was that it gave me a reason to try out the Password Analysis and Cracking Kit (PACK). PACK is a Python-based wordlist (in my case password) analysis script and I would recommend this tool for both password analysis as well as taking a peak into your large wordlists to see if they are valuable or not based on what you’re trying to crack (i.e. 7 character passwords don’t make sense for WPA-PSK breaking). The script not only shows you the length by distribution (which would be trivial in Excel, I know), but it also analyzes the character sets, complexity, and shows what Hashcat masks would work best to break X percentage of the passwords in the list.

Here’s what PACK had to say about my Google sample of 790,462 passwords:

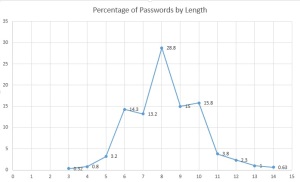

- Length distribution (in the graphic below) showed that the largest percentage of passwords was in the 6-10 character range which is expected. What I didn’t expect was that 8-10 would make up a majority of the passwords by length (~59.6% of all passwords)

- Complexity by percentage was highest for lower alpha-numeric followed by lower alpha-only (~79% of all passwords)

- The simple masks show that a majority of the passwords are a string followed by digit (root + appendage as mentioned above) and a simple string (~66% of all passwords)

- The advanced masks for Hashcat that break the most passwords (~12% of all passwords) are ?l?l?l?l?l?l?l?l and ?l?l?l?l?l?l, which means 12% of the passwords are 6 or 8 character alpha-only passwords

So what did the results show? Well, I think they showed what I thought they would show…passwords that people chose are both predictable and unchanged over the last 7+ years. In addition to my research, KoreLogic Security had a good presentation on password topology histograms from corporate pen tests that showed results that were similar to those above. The one difference that stood out from my research was that I was breaking LM passwords back in 2006-7 so I wasn’t as concerned with case-permutations (I didn’t care where the upper alpha character was as that was trivial to determine if needed), and second, the Google sample I analyzed seemed to favor all lower case roots. For comparison, my top 3 masks and the Kore top 3 masks were:

(Kore* – My Sample)

- ?u?l?l?l?l?l?d?d – ?l?l?l?l?l?l?l?l

- ?u?l?l?l?l?l?l?d?d – ?l?l?l?l?l?l

- ?u?l?l?l?d?d?d?d – ?l?l?l?l?l?l?l?l?l

*Note I’m only using the Kore Fortune 100 sample, the second sample in their set simply added a special character to the last position of the mask.

What this comparison showed was that corporate passwords appear to be more complex but just as long as the passwords people generally choose for websites (i.e. Gmail, Ymail, etc.) for the top 3 masks and that the techniques for breaking non-corporate and corporate passwords may need to be adjusted depending on the target at-hand. What this also showed was that corporate users tend to hover around a few topologies of passwords and my sample showed a more even distribution of masks. For example, the top 3 masks from the Kore presentation represent ~36% of all passwords from the sample and mine represent only ~16%. I’d have to get 10 masks deep to get to 36% of all passwords. It also showed that people tend to choose a path of least resistance to creating a password. Many websites and web services generally do not require password complexity, hence what I believe is driving the higher number of all lower alpha passwords in my sample versus my early research and the more recent Kore research into corporate passwords.

Finally, I’d like to end this with an explanation of the title of the post. While in the “less than a 10th of a percent area of the passwords in my sample”, some interesting passphrases emerged especially in the 20+ character range. Besides “ilovejustinbeiber” I thought the “passwordispassword” password spoke volumes about how users view their passwords…as a hindrance to getting what they want or where they need to go.

Tl;dr – passwords still suck as an authentication mechanism and our users aren’t going to go out of their way to increase security.

Comments